Sampling Distribution

Introduction

This article is the theoretical bridge that allows us to use information from a single sample to make educated guesses about an entire population. It is the backbone of hypothesis testing and confidence intervals, giving statistical inference its power and rigor.

In real life situations it is often impossible to calculate statistics such as mean and variance for the whole population. Instead we may only be able to draw a sample from the whole population, calculate statistics over it, and project it on the whole population. Of course, sample statistics won’t correspond fully to that of the whole population, and it may vary among different samples, since each sample is drawn independently.

From here, a definition of sampling distribution arises, which is the probability distribution of a statistic (like the mean, variance, or standard deviation) that would be obtained by taking an infinite number of random samples of the same size from a given population.

Although we never actually take an infinite number of samples, this hypothetical distribution provides a critical framework. It tells us what to expect from our sample statistic and how likely it is to be close to the true population parameter.

The Central Limit Theorem (CLT)

The Central Limit Theorem (CLT) is arguably the most important theorem in all of statistics, and it is the reason sampling distributions are so useful. It states that for a large sample size (generally $n \geq 30$), the sampling distribution of the mean will be approximately normally distributed, regardless of the shape of the original population’s distribution.

This is a profound statement. It means that even if the population data is heavily skewed or not normally distributed, the distribution of our sample means will always look like a predictable bell-shaped curve.

The CLT provides us with key properties of this sampling distribution such as the mean of the sampling distribution and its standard error - the expected difference between the sample mean and the population mean.

Why It Matters for Inference

The sampling distribution is what gives us the ability to move from describing a sample to making inferences about a population. It answers the fundamental question of inferential statistics: “Is our sample result just due to random chance, or does it represent a true effect in the population?”

Confidence Intervals: The sampling distribution allows us to construct a confidence interval around our sample mean using the standard error. Based on the known properties of the normal distribution, we can say with a certain level of confidence (e.g., 95%) that the true population mean lies within a specific range.

Hypothesis Testing: When we perform a hypothesis test, we are essentially asking how likely it is to observe our sample result if the null hypothesis were true. The sampling distribution tells us the probability of observing our sample mean by chance alone. This probability, known as the p-value, allows us to make a decision about whether to reject the null hypothesis.

The concept of a sampling distribution is not limited to the mean. A sampling distribution is the theoretical probability distribution of any statistic calculated from a sample. While the Central Limit Theorem gives us a perfect, predictable outcome for the mean, we can and do create sampling distributions for other statistics as well, such as:

- The sampling distribution of the median.

- The sampling distribution of the standard deviation (often called the Chi-squared distribution).

- The sampling distribution of a proportion.

For these types of statistics however the sampling distribution might not be normal. In these cases, we rely on other methods, such as bootstrapping, to create an empirical sampling distribution. Bootstrapping involves taking many subsamples from your single original sample to simulate the process of drawing from a population.

The Mathematics of the Sampling Distribution

Sample Mean

Expectation of the sample mean

As stated above, if we randomly draw $n$ samples from the population and calculate the mean value of each, we’ll likely get different results. Here, the mean of a sample (signed as $\bar X$) becomes a random variable. Yet it is possible to calculate the expected value of $\bar X$ (in other words the mean of the sample mean), and its variance. For the expected value we have:

\[\begin{align*} E[\bar X] &= E[\frac{x_1 + x_2 + ... + x_n}{n}]\\ &= \frac{1}{n}E[x_1 + x_2 + ... + x_n]\\ &= \frac{1}{n}(E[x_1] + E[x_2] + ... + E[x_n]) \end{align*}\]The expectation of each of the individually drawn values is equal to the mean of the population $\mu$, so:

\[E[\bar X] = \frac{1}{n}(\mu + \mu + ... + \mu) = \frac{n \mu}{n} = \mu\]Eventually the expected value of the sample mean is equal to the mean of the population.

Variance of the sample mean

Before moving to the expression of the variance of the sample mean it is worth to mention that the constant is getting squared after moving from the expression of variance:

\[\begin{align*} \text{Var}(aX) &= E[(aX - E[aX])^2]\\ &= E[(aX - aE[X])^2]\\ &= E[a^2(X - E[X])^2]\\ &= a^2 E[(X - E[X])^2]\\ &= a^2 Var(X) \end{align*}\]Remembering this, we can calculate the variance of the sample mean:

\[\begin{align*} \text{Var}(\bar X) &= Var(\frac{x_1 + x_2 + ... + x_n}{n})\\ &= \frac{1}{n^2}Var(x_1 + x_2 + ... + x_n)\\ &= E[a^2(X - E[X])^2]\\ &= \frac{1}{n^2}(Var(x_1) + Var(x_2) + ... + Var(x_n))) \end{align*}\]The variance of each of the individually drawn values is equal to the variance of the population $\sigma^2$, so:

\[\text{Var}(\bar X) = \frac{1}{n^2}(\sigma^2 + \sigma^2 + ... + \sigma^2) = \frac{n \sigma^2}{n^2} = \frac{\sigma^2}{n}\]The variance of the sample mean is much less than the variance of the population which means that the sample mean won’t be much different in different independently drawn samples. Taking into consideration the Central Limit Theorem, it makes sense because the sample mean will tend to be near the true mean as the number of samples increases.

The equivalent of standard deviation for sample distribution is called standard error which essentially is the estimate of the error of making assumptions about the true mean.

\[\text{SE} = \frac{\sigma}{\sqrt{n}}\]where $\sigma$ is the standard deviation of the population. This measure is usually not known, therefore an estimation based on the sample variance is used, as seen below.

Sample variance vs estimation of the true variance

It should be stated that the sample variance is not quite the true representative of the population’s variance, since we usually know only the expectation of the true mean (the mean of the sample) but not the true mean itself. As was discussed in the previous section, the sample mean has its own variance which is equal to the true variance divided by the number of samples. Thus, the true variance will have to incorporate this metric, as well as the variance of the sample.

\[\sigma^2 = s^2 + \frac{\sigma^2}{n}\]where $s^2$ is the sample variance which we can directly from a sample. By little rearrangement we have:

\[s^2 = \sigma^2 - \frac{\sigma^2}{n} = \frac{n \sigma^2 - \sigma^2}{n} = \sigma^2 \cdot \frac{n-1}{n}\]From this we get the unbiased estimate of the true variance:

\[\sigma^2 = \frac{s^2}{\frac{n-1}{n}} = \frac{\sum_{i=1}^n(x_i-\bar x)^2}{n-1}\]Confidence interval and margin of error

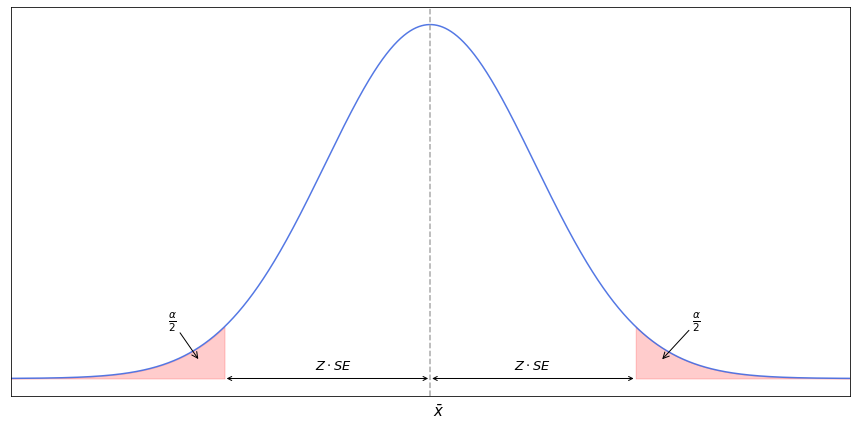

Using the notion of standard error of the sample mean, for a certain confidence level it is possible to define the bounds for the region where the true mean might be - the confidence interval. Depending on the sample mean different samples may produce different confidence intervals, therefore the confidence level is the probability that a randomly drawn sample will produce a confidence interval containing the true mean. A common misconception is that the confidence level is the probability that the true mean lies within a certain confidence interval.

The confidence interval is expressed as the region around the point estimate of the mean:

\[(\bar X - Z \cdot SE; \bar X + Z \cdot SE)\]where $Z$ is the critical value for a given significance level (confidence level minus 1). For the normal distribution the z-value tells how many standard deviations from the mean a certain value is. Z-value can be used if it is assumed that the population has normal distribution, and if its standard deviation is known. If the population’s standard deviation is unknown, it is estimated from the sample, as described in the previous section, only in this case t-value (derived from Student’s t-distribution) is used instead of z-value. In addition, t-value is typically used if the size of the sample is less than 30. While $z$-value follows normal distribution with the mean value of 0, t-distribution has similar shape but with thicker tails so under the same significance level it allows the test statistic to stray further from the true mean. At any rate, for a certain significance level it is possible to get z- or t-statistic from a table of precomputed values. When estimating the confidence interval, the table for the two-tailed distribution should be used, as the area of the smallest probability is located to the both sides of the mean estimation. Below is the distribution plot of a confidence interval.

As we see, the area covered by the significance level is split in halves and occupies the farthest regions of the distribution.

The expression $z \cdot SE$ is the margin of error, and it depends only on the populations’s standard deviation, number of the samples, and the selected confidence level.