Imaginary number and rotation of vectors

Introduction

The imaginary number is a mathematical concept (denoted as $i$) that extends the real number system to include the square root of -1, hence $i^2 -1$. It does not have a direct connection with the real world and might appear useless but it offers a powerful and elegant way to represent and manipulate certain mathematical quantities.

The introduction of imaginary numbers allows us to solve equations that would be impossible to solve with only real numbers. This is similar to solving the equations which have a negative root in the sense that the negative numbers do not represent the quantities of the real world either. However people became more accustomed and comfortable in using them on a regular basis.

Imaginary number and rotation of vectors

A useful property of the imaginary numbers lies in the fact that they can be used in vector rotation in the space of complex numbers.

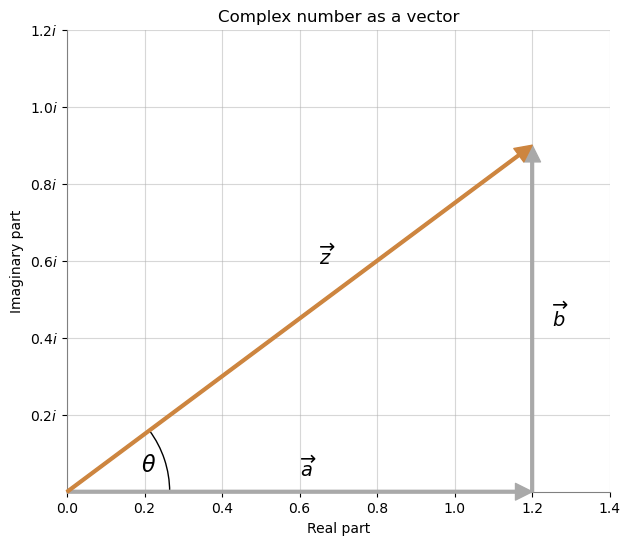

Recall that a complex number is a number that comprises both a real part and an imaginary part. It is expressed in the form $z=a+bi$, where $a$ and $b$ are real numbers, and $i$ is the imaginary unit.

A complex number can be represented as a vector in two-dimensional space where the axes correspond to the real and imaginary parts of the number. It happens that multiplying a complex number by $e^{i \alpha}$ results in rotation of this vector by an angle $\alpha$ around the origin. Below is an explanation as to why it happens.

Euler’s formula

First we need to understand Euler’s formula, which is a remarkable mathematical result that connects exponential functions, trigonometric functions, and complex numbers. This is how it looks:

\[e^{i \theta} = \cos(\theta) + i \sin(\theta)\]Its derivation involves the use of power series, calculus, and complex analysis.

Let’s start with the exponential function $e^{x}$. Using Taylor series it is possible to represent this function as an infinite sum of polynomials. By selecting the point of approximation as 0 we simplify it to Maclaurin series, and the exponential function gets the following form:

\[e^x = 1 + x + \frac{x^2}{2!} + \frac{x^3}{3!} + \frac{x^4}{4!} + ...\]Similarly, let’s express the sine and cosine functions by Maclaurin series as well:

\[\sin(x) = x - \frac{x^3}{3!} + \frac{x^5}{5!} - \frac{x^7}{7!} + ...\] \[\cos(x) = 1 - \frac{x^2}{2!} + \frac{x^4}{4!} - \frac{x^6}{6!} + ...\]Now, let’s return to the exponential function and include the imaginary number into the power. The decomposition into the sum of components will look like this:

\[e^{ix} = 1 + ix - \frac{x^2}{2!} - \frac{ix^3}{3!} + \frac{x^4}{4!} + ...\]Then it is possible to group into separate components the imaginary and the real parts of the equation:

\[e^{ix} = (1 - \frac{x^2}{2!} + \frac{x^4}{4!} - ...) + i(x - \frac{x^3}{3!} + \frac{x^5}{5!} - ...)\]From which we should be able to recognize the Maclaurin series of size and cosine functions displayed above.

Trigonometric identities in terms of exponential functions

Using the Eurler’s formula it is possible to express both sine and cosine functions by using complex exponentials only.

Remember that cosine is an even function, while sine is an odd one. Meaning that $\cos(-\theta)=\cos(\theta)$ and $\sin(-\theta)=-\sin(\theta)$. Therefore,

\[e^{-i \theta} = \cos(-\theta) + i \sin(-\theta) = \cos(\theta) - i \sin(\theta)\]If we take the original Euler’s formula and add $e^{-i \theta}$ to both left and right side we will get the following:

\[e^{i \theta} + e^{-i \theta} = \cos(\theta) + i \sin(\theta) + \left( \cos(\theta) - i \sin(\theta) \right) = 2 \cos(\theta)\] \[\cos(\theta) = \frac{e^{i \theta} + e^{-i \theta}}{2}\]Similarly, for sine we can get this by taking the difference instead of adding as we did with the cosine:

\[\sin(\theta) = \frac{e^{i \theta} - e^{-i \theta}}{2i}\]Complex number in a vector form

In the complex plane, the horizontal axis traditionally represents the real numbers, and the vertical axis represents the imaginary numbers. Although the real and imaginary axes are not orthogonal in the traditional sense they exhibit certain mathematical properties related to conjugation which is why they are often described as perpendicular or orthogonal in a mathematical context.

Complex numbers represented via Euler’s formula

Complex numbers can be represented in polar form using Euler’s formula. For a complex number $z=a+bi$ it will look like this:

\[z = r(\cos(\theta) + i \sin(\theta))\]where $r$ is the magnitude of the complex number, and $\theta$ is the angle which the vector of this complex number makes with the x-axis.

From the image above $\cos (\theta)$ is the length of $\overrightarrow{a}$ divided by the length of $\overrightarrow{z}$. Similarly, $\sin (\theta)$ is the length of $\overrightarrow{b}$ divided by the length of $\overrightarrow{z}$. Since $b$ is the imaginary part of the complex number, it also has to be multiplied by $i$.

By plugging in these pieces into the equation above we can see the equality:

\[z = r(\cos(\theta) + i \sin(\theta)) = r(\frac{a}{r} + i \frac{b}{r}) = a + bi\]We can also see that

\[z = r(\cos(\theta) + i \sin(\theta)) = r e^{i \theta}\]Rotation the in complex space and Euler identity

Now what happens if the complex number is multiplied by $e^{i\alpha}$.

\[z \cdot e^{i\alpha} = r e^{i \theta} \cdot e^{i\alpha} = r e^{i (\theta + \alpha)}\]This is only different from the original number represented via the Euler number by the angle. Instead of $\theta$ we get $\theta + \alpha$, which is the operation of rotation.

Below is the visualization on how the vector representing the complex number $z$ can change its direction when multiplied by $e^{i\alpha}$ with the different value of $\alpha$. The original number is simply 1. It means that its component $a$ is equal to 1 and $b$ is equal to 0.

The bigger the value of $\alpha$ - the greater the angle of rotation. The magnitude $r$ of the vector stays the same.

The reason for the counterclockwise rotation in the given example is rooted in the choice of the mathematical convention for the direction of angles in the complex plane. In the standard Cartesian coordinate system, angles are measured counterclockwise from the positive x-axis.

Notice how the vector performs 180 degrees rotation if $\alpha$ is equal to $\pi$. It is equivalent to multiplying by -1, and thus

\[e^{i\pi}=-1\]The slight modification of this equation is known as Euler identity.

\[e^{i\pi} + 1 = 0\]The common fact is that $\pi$ is the ratio of circle circumference to its diameter, hence the ratio of circumference to its radius is $2 \pi$. In other words the vector representing the radius needs $2 \pi$ of its length in order to complete the whole length of the circumference. This fact is in total sync with the idea of 360 degrees rotation described above.

Also since in the example above $z$ is simply 1 ($\theta$ is 0), via the Euler’s formula it can be seen how the relationship between $\sin (x)$ and $\cos (x)$ looks like a circle if $x$ assumes values from 0 to $2\pi$.