Change of basis

Let’s recall that the basis is a set of linearly independent vectors which form the full span of vector space. With regard to matrices the basis can be viewed as a set of linearly independent vectors which can be used to form vectors of a matrix. The most common basis is a set of $n$ unit vectors, where $n$ is the number of dimensions, since they can easily be manipulated by adding and scaling into forming other vectors. From this follows that the basis defines the coordinate system in which the vectors of a matrix turn out to be, and the actual transformation encoded within the matrix is dependent on the choice of coordinate system.

Vector in different bases

Imagine yourself looking for a correct way in some unknown part of the city and someone saying to you that you would have to go to the right in order to reach your destination. The problem is that you don’t know which “right” is meant: relative to you or to your helper. Same goes with vectors and their bases - one and the same transformation may be described with different coordinate systems.

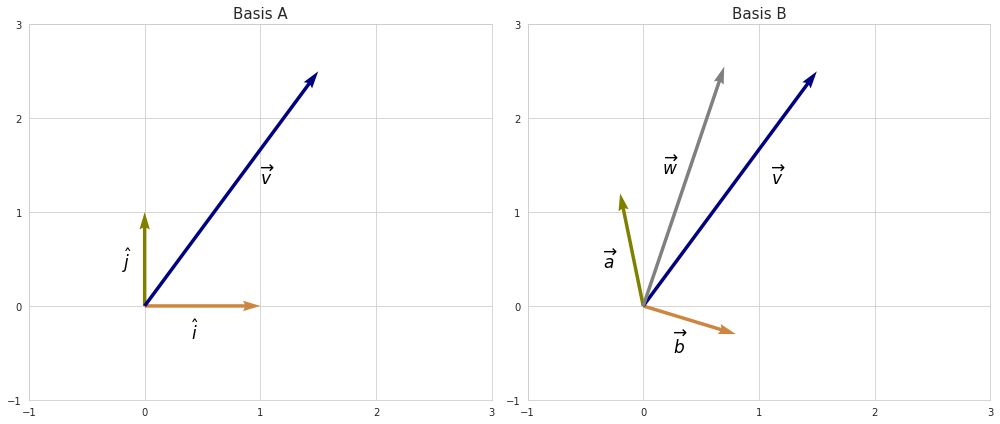

Let’s take a look at simple example:

Vector $v$ can be described using the basis of unit vectors (basis A) just like that:

\[\left[\begin{array}{c} 1.5 \\ 2.5 \\ \end{array} \right]\]However with a different basis, as in basis B, the same vector definition will produce a different linear transformation - in our case vector $w$. In order to get the same one as we have in basis A we would need to account for the existing basis.

We can represent basis vectors in B with basis vectors of A by taking respective linear combinations of $\hat{j}$ and $\hat{i}$ and forming a matrix with them:

\[\left[\begin{array}{cc} \\ a & b \\ \\ \end{array} \right] = \left[\begin{array}{cc} \\ k_{1}i + k_{2}j & k_{3}i + k_{4}j \\ \\ \end{array} \right]\]The resulting matrix (let’s call it $Q$), translates linear transformation set in basis B into a coordinate system expressed by basis A. In the example above multiplying vector $v$ with $Q$ results into vector $w$ because the elements of $v$ scale vectors $a$ and $b$ instead of $\hat{i}$ and $\hat{j}$.

While matrix $Q$ allows to switch from basis B to basis A, its iverse $Q^{-1}$ does exactly the opposite. Therefore, if we multiply vector $v$ with $Q^{-1}$ we would obtain the same vector but expressed in the coordinate system of basis B.

Linear transformation in different bases

Now what if we want to represent the same type of linear transformation which can be applied to any vector with a different basis? Recall that any type of linear transformation in $n$-dimensional space can be described by $n \times n$ matrix, so the problem boils down to translating a matrix from one basis into another.

Say we have our linear transformation captured in some matrix $X$ defined in space with basis A, and transformation matrix $Q$ which translates vectors from basis B to basis A. In this case we do the following:

- Take $Q$ in order to have transformations in basis B represented with basis A.

- Multiply $Q$ with $X$ on the left. This will produce the transformation in basis B that we need but it will be expressed in coordinate terms of basis A.

- Multiply the result from the previous step with $Q^{-1}$ on the left in order to have our transformation represented with basis B.

$X_B = Q^{-1}X_{A}Q$

So any vector space may be defined with multiple different basis vectors. In practice shifting from one basis to another is often useful for simplifying matrix computations by transforming matrices into diagonal form. A diagonal matrix has nice properties when it comes to solving systems of linear equations, since each equation can be easily solved without performing additional operations. Singular value decomposition utilizes this technique in its core.