Understanding derivatives

Building intuition

Derivatives are mainly used in the context of measuring rate of change between variables. Plainly speaking, it allows to see how one variable changes if another variable or variables also change.

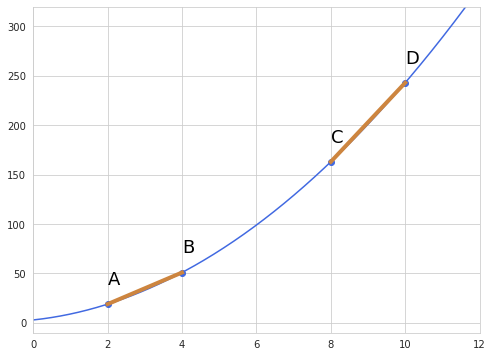

For understanding derivatives it is good to know what the slope of a function is and how it is measured. The slope generally shows the ratio of changes ($\frac{\Delta y}{\Delta x}$) between variables in two different points. In real life, however, it is rare that a function represents a straight line, as the slope changes over time. Let’s look at the function described by the following curve:

We can look at the points A and B, calculate the ratio of changes, then do the same for the points C and D, and come up with rather different slopes. We can see that the slope between points A and B is less steep than between points C and D. Moreover, the slope along the whole line is not constant as well.

So here is where calculus comes really handy - using derivatives we can measure instantaneous slope, that is the rate of change at any specific point of a line. Intuitively, instantaneous rate of change is the relation of the change in $y$ to the change in $x$ when the change in $x$ is infinitely small ($\displaystyle{\lim_{\Delta x \to 0}}$).

The common notation (Leibniz’s notation) for instantaneous rate of change in calculus is this - $\frac{dx}{dy}$, and the derivative function for $f(x)$ would be noted as $f’(x)$ (Lagrange’s notation). By expressing derivative through the term of limit we get the following equation:

$f’(x) = \displaystyle{\lim_{h \to 0}}\frac{f(x_0 + h) - f(x_0)}{h}$

Differentiability of a function

It is worth to note that a function may be non-differentiable if it has points of discontinuity within its domain. In addition, in order to be differentiable at a certain point, both one-sided limits at that point must be equal:

$\displaystyle{\lim_{x \to c^{-}}}\frac{f(x)-f(c)}{x-c} = \displaystyle{\lim_{x \to c^{+}}}\frac{f(x)-f(c)}{x-c}$

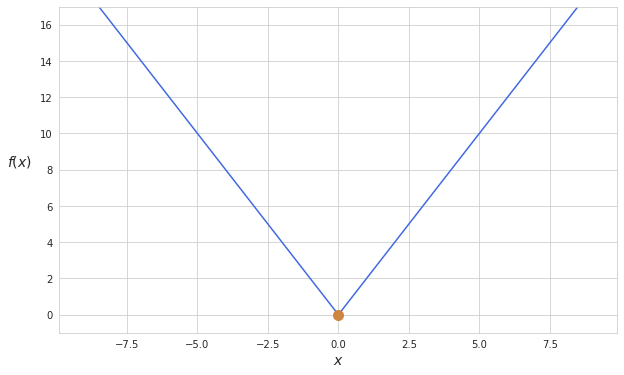

Plainly speaking, these are the conditions under which a slope at a certain point would exist. Looking at the example below it is clear that the limits of a function approaching the point from both directions are different, therefore, it is impossible to get the ratio of changes at that particular point. Hence the function is non-differentiable.

Calculating derivatives

For future reference, below I include the table of the most commonly used transformations when calculating derivatives.

| $y = f(x)$ | $\frac{dx}{dy} = f’(x)$ |

|---|---|

| $k$, any constant | 0 |

| $x$ | 1 |

| $x^2$ | $2x$ |

| $x^n$, any constant $n$ | $n(x)^{n-1}$ |

| $a^x$ | $a^x \ln a$ |

| $e^x$ | $e^x$ |

| $e^{kx}$ | $ke^{kx}$ |

| $\ln x$ | $\frac{1}{x}$ |

| $\log_{a} x$ | $\frac{1}{x\ln (a)}$ |

| $f(x)g(x)$ | $f’(x)g(x) + g’(x)f(x)$ |

| $\frac{\mu(x)}{\upsilon(x)}$ | $\frac{\mu’(x) \upsilon(x) - \upsilon’(x) \mu(x)}{[\upsilon(x)]^2}$ |

| $f(g(x))$ | $f’(g(x)) g’(x)$ |

Second derivative

The second derivative of a function is simply the derivative of the function’s derivative. If the first derivative is understood as the ratio of change, the second derivative is the ratio of change in ratio of change, in other words - acceleration.

Let’s consider, for example, the function $f(x)=x^3+2x^2$. Its first derivative is $f’(x)=3x^2+4x$. To find its second derivative, $f’’$, we need to differentiate $f’$. When we do this, we find that $f’’ (x)=6x+4$.

Leibniz’s notation for second derivative is $\frac{d^2y}{dx^2}$. For example, the Leibniz notation for the second derivative of $x^3+2x^2$ is $\frac{d^2}{dx^2}(x^3+2x^2)$.

Gradient

Gradient is a multi-variable generalization of derivative. If a function has multiple variables we can take derivatives with respect to each variable while treating others as constants. Therefore, for a multivariable function it is possible to find the instantaneous rate of change with respect to each variable. At each point of a function the gradient would represent a vector, whose elements would be the partial derivatives of this function, which in turn would show the slope in each dimension.